“Welcome to Wounded Knee.”

I was worried about driving through Indian country before I left for my cross-country road trip in the summer of 2010. I wanted to go to Wounded Knee, South Dakota (the site of a terrible slaughter in 1890) for some research for a novel I’m working on. I had never been to Indian country and had no idea what to expect.

I did know though if I made it out there I had to be subtle. I read an article that said the Indians are sick of being studied by sociologists, journalists and other researchers.

So before I left New Jersey I called the police department at the Pine Ridge Reservation (where Wounded Knee is). A woman answered the phone and I told her I would be driving through there in a few weeks and that I was white and from the east coast.

“I’m just, you know, a little concerned. Will I have any problems?” I asked her.

“No,” she said, laughing. “Just smile and waive hi to everyone!”

Cool, I’m thinking, great!

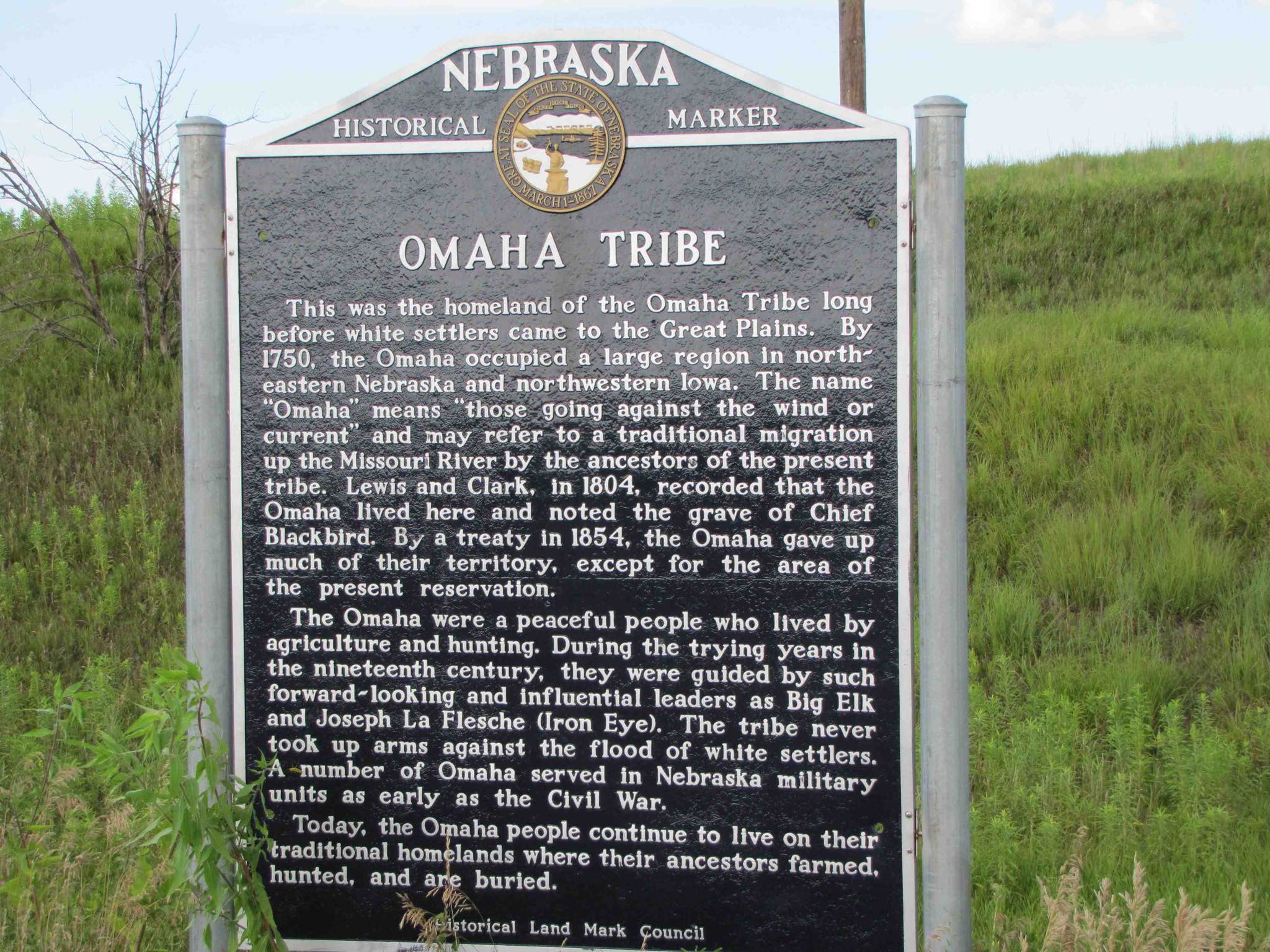

I got on the road and by the end of July was close to Wounded Knee. I left Ponca, Nebraska, in the northeast corner of the state, after spending the previous day driving south to north on Highway 75 that parallels the Missouri River and Iowa border.

I’ve driven across the States three times in my life and Highway 75 was a treat. States like Nebraska can be incredibly boring but not this road. I drove past acres of farmland, rolling fields with corn and other crops. Every now and then a huge, lone tree or cluster of trees would punctuate the fields, standing out like a surreal marker, grabbing your attention.

The Missouri River

Nebraska

By around 7 p.m. I had reached a tiny town, Vetal, South Dakota. I was on Highway 18, about 50 miles south of Interstate 90 (one of the main highways that traverses the country). Gas stations were scarce on 18 so I was filling up my tank whenever it reached half-empty. I desperately needed to get out of my car, stretch my legs and drink a beer so I stopped at the R-Bar.

Vetal, South Dakota

A wood sculpture at the Fort Randall Dam, about 200 miles east of Vetal

I started talking to the bartender and told her about my trip. “I’m on my way to Wounded Knee.”

“That’s not a good idea,” she said.

“Why?”

“Well it’s getting late and will be dark soon. Just for your safety, in case you break down.”

Now I was worried. The woman at the police station told me I’d be fine but here was another local telling me I could have a problem. Screw it, I thought, I may never be here again and I really want to see this place.

I had plugged Wounded Knee into my GPS and was about an hour away. History has always been one of my favorite subjects and I studied it a lot in high school and college. But once I started doing my own research I was shocked to discover just how horribly the Indians were treated and how much information was either glossed over or simply omitted from my classes.

By the late 1880s the Indians were doomed. The Plains Indian Wars, that lasted nearly four decades, were winding down and many Indians had been herded onto reservations. The land we put them on was awful and most of it was not suitable for farming. And many of the Indians who were hunters and gatherers didn’t know how to farm. Starvation and disease were rampant.

A religious movement, called the Ghost Dance, swept through several reservations out west. In around 1870 a northern Paiute named Tavibo prophesied the animals and sweet grass would once again flourish, dead Indians would return and the whites would get swallowed up by the earth.

Another Paiute, Wovoka (who may have been Tavibo’s son, it’s not known for sure) began to make similar prophesies in the late 1880s. He also told Indians to cooperate with the whites and live a morally clean life. The Indians held elaborate ceremonies, chanted and sang, danced in circles and called out the names of their deceased loved ones as part of the Ghost Dance.

The white agents who ran the reservations saw these gatherings, didn’t understand what was happening and got nervous. The respected Lakota leader Sitting Bull was killed by Indian police, backed by soldiers, during a protest when they went to arrest him in December of 1890.

A few days later a force of 500 soldiers confronted Big Foot and his tribe (ardent followers of the Ghost Dance) on the Pine Ridge reservation. Sick with pneumonia Big Foot wasn’t looking for a fight and was flying a white flag. On the night of December 28th the Indians, camped out near Wounded Knee Creek, found themselves surrounded by the US Army.

The soldiers set up powerful, wagon-wheel mounted Hotchkiss guns on a bluff overlooking the encampment. The next morning the soldiers began confiscating the Indians’ weapons. What happened next is unclear but apparently a weapon accidentally discharged and then the Army unleashed a deadly barrage of gunfire.

Within minutes nearly 370 Lakota were killed, many of them shot by the Hotchkiss guns while trying to find shelter against the creek bank. Many of the dead included women and children that tried to flee but were cut down by pursuing soldiers. As word of the slaughter spread throughout other reservations many Indians realized they were finally defeated and stopped any hostilities.

Driving through Indian country is like driving through a land time, and America, forgot. Before it got dark I drove through the Rosebud reservation, right next door to Pine Ridge. The town was a shabby assortment of trailer homes and dilapidated houses. A huge sign on the fence of an apartment building said: “If any residents are found to have alcohol or drugs in their possession on this property they will have to leave immediately.” Mangy, stray dogs roamed the streets.

When I got to Pine Ridge my GPS sent me off the road and up a bluff. I found myself driving on two rutted-out tire tracks up a small hill. When I stopped at the top my GPS said, “You have arrived at your destination.”

It was dark by now. I got out of my car and saw a small church behind me. It had a stone, arched entranceway I walked through. There was a small cemetery next to the church and I wondered if the graves were victims of the Wounded Knee massacre so I started reading the tombstones. Some of the deceased had died in the 1920s and 30s but there were also markers commemorating the Indians killed on that terrible day here.

Moonrise over Wounded Knee

I went back to my car and stood near the edge of the bluff. A full moon was starting to rise and I could see the barren, uneven landscape before me and hills in the distance. Then I noticed a man walking up the side of the bluff. He wore jeans but no shirt. His long hair was tied in a ponytail and fell down to his waist.

I hope this guy is cool, I thought. Then I saw a woman and small child, about six or seven years old, following him. He has to be, I thought, with a kid here.

He approached the church, stood in front of the arched entranceway, pressed his hands together as if in prayer and nodded forward. Then he turned and walked over to me.

“Welcome to Wounded Knee,” he said, putting his hand out to shake mine.

“Thanks,” I replied.

“My name is Russell. I’m a full-blooded Lakota and was born and raised here. If you have any questions, feel free to ask.”

“Well,” I began, nervous and not exactly knowing what to say. “I know a terrible slaughter happened here. I guess I just wanted to come here and see this place. Check it out.”

“Yes, a terrible slaughter did happen here,” he said. He proceeded to tell me the history of Wounded Knee and that the bluff we were standing on was where the army set up their Hotchkiss guns.

He pointed to the landscape in front of us. “Most of the Indians were down there. Some of the men, who still had their weapons, fought back. But the army had the high ground and superior firepower. We never had a chance.”

As we spoke the full moon rose higher. It was a warm, July night and the mosquitos were eating me alive. But not once did I see Russell, who wasn’t wearing a shirt, swat away or smack part of his body because of a mosquito bite. I wondered if some sort of magical, Lakota force field protected him from the mosquitos.

Russell said Indians from around the country still came to Wounded Knee to pay their respects to the dead. He then told me about the uprising here in 1973, when activists and members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) took over the area to protest corrupt members of the tribal council and the racism they faced outside of Pine Ridge.

The siege lasted 71 days. When it was over two Indian activists were killed and one federal agent was shot and paralyzed. Internal fighting at Pine Ridge continued for several years and by 1976 the reservation had the highest per capita murder rate in America (the dead included two FBI agents).

Russell then told me how the current tribal council wanted to spend federal money to build a new road through Wounded Knee, right below the bluff we stood on.

“Why? Is it needed?” I asked.

“No, not at all,” he began. “And many Indians are upset about it. This is holy land. But they want to show the government they can be responsible and build things with whatever money they can get. And steal some at the same time.”

We then saw one of his friends at the bottom of the bluff, hanging out at a huge propane tank, so we went down to see him.

Russell introduced me to him and he said his name was Buddy.

We hung out for about another hour, talking about the area and then I started telling them about my road trip and how I left New Jersey and was on my way to Vancouver Island.

Buddy then turned to me. “So I just have one question for you.”

“Okay,” I replied.

“What are you doing out here in the middle of nowhere?”

It was the perfect question, one that I could only smile and shrug at.